Ideas and Execution

On the relationship between the ideas that drive creation and the creation itself:

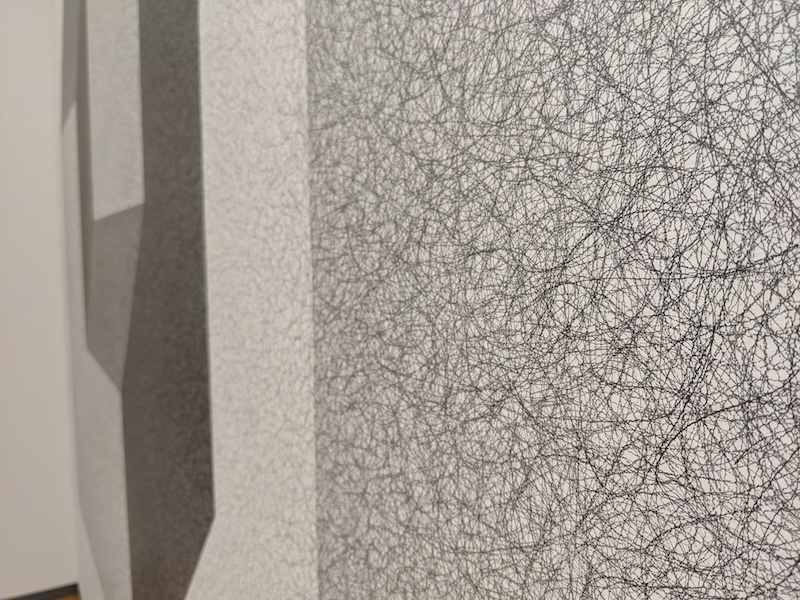

Almost five years ago, I went to the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCa) and saw Sol LeWitt’s installation there. He had created over 100 wall drawings across 27,000 square feet of space, made of three stories of narrow hallways and expansive rooms with drawings on all sides. The work is driven by shapes and lines; there was mathematical rigor to every drawing, inspired by geometry and simple rules. They are accompanied by a short description:

Wall Drawing 1180: Within a four-meter circle, draw 10,000 black straight lines and 10,000 black not straight lines. All lines are randomly spaced and equally distributed.

But “accompanied” is not the right word for it.

It’s common for artists to use geometry. It was the rigor that was so impressive. The descriptions of the artwork were no longer than a few paragraphs, and usually only one or two sentences. All precise and meticulous.

Wall Drawing 46: Vertical lines, not straight, not touching, covering the wall evenly.

He started his first drawings with a series of parallel, straight lines. The work grew to include minimalist geometric shapes driven by straight lines, drawn with pencil or pen with exacting geometry. As his career progressed, he incorporated more color and complex patterns into his art; more bold lines, vibrant colors, irregular shapes, different materials. All driven by initial instructions which he followed meticulously.

Wall Drawing 38: Tissue paper cut into 4-cm squares and inserted into holes in the gray pegboard walls. All holes in the walls are filled randomly.

Closer to the end of his life, his work became increasingly collaborative. He viewed the rules as art in its own right; he would work with other artists and they would execute the complex instructions, while bringing their own unique perspective and style to the drawings. Each floor of Mass MoCa was a phase in his career, and the final floor included his collaborations with other artists. You could see the subtle departure from the rest of the work; more vibrant colors, a new material, but keeping the exacting rigor that LeWitt maintained.

There is a story in the evolution of his work. He started individualistic, simple, regimented. His last works were collaborative, with diverse mediums and an expansive visual vocabulary.

The instructions themselves are elegant and beautiful. The work clearly starts there. But it’s not only that. They are only abstract words; the execution brought them to life. The work didn’t exist without the painstaking execution.

Let’s say you are drawing 10,000 straight black lines, and each line takes about 10 seconds each. That would mean almost 28 hours of meticulous focus. And that would be very fast, since each line must be evenly spaced and equally distributed.

There is a lesson of “craft” in this space. The vision, the execution, and the constant exchange between the two. It is somewhere between science and art. The analytical see the geometry; the artistic see the symmetry. It is not definitively one or the other. Somewhere between them is the craft.

The most incredible man-made achievements can be described in this way. Take an Eames lounge chair as an example: curved plywood, thick leather cushions, three distinct pieces. A moleskin notebook: oil-cloth bound cover, elastic closure, compact. A Montblanc pen: handcrafted ribs, iconic emblem, sleek body. They can be described with simple words, but it’s not only the words that make them beautiful. They are beautiful because their craftsmanship starts with their description and continues with their execution.

Everyone starts where LeWitt did. Your early vocabulary starts narrow and elementary, separate from others. As you have more interactions with the work, it changes your vocabulary and your vocabulary changes the work. You start seeing what makes something have deep quality and the beauty in collaborating on that vision.

There’s a widely known trap in the world for people without experience. They will say things like, “that [incredible] product would have existed no matter what, they were just the first to think of it.” This is not true. There is a feedback mechanism between what exists in the current moment and the way people view the world. You would not think to start an online store before the Internet. The reality is that the idea was only the beginning of a journey that created the product.

The people who have experience will sometimes say the opposite, and they are also wrong. The idea matters. It’s not only about execution. The two shouldn’t be separated; the idea should evolve over time with the work. The idea drives the early work, and the early work changes the idea, and so on. It is the interchange between the two that makes craft. It’s taking feedback from the work and allowing it to change the idea. The vocabulary evolves with the work. If you trivialize the idea, the work will suffer. And vice versa.

Another way people commonly say this is that it’s about the journey, not the destination. This is not entirely true. The destination is the inspiration; it’s why you started in the first place. It’s why you keep going. Your experience along the way will change your expectations, things will happen that are beyond your control, and your destination will change. The destination still matters.

The hardest part is allowing the idea to change with the work, while making sure the idea keeps its importance.

If you have thoughts you would like to share, feel free to email me at [email protected].

Related

There are no essays which link to this.